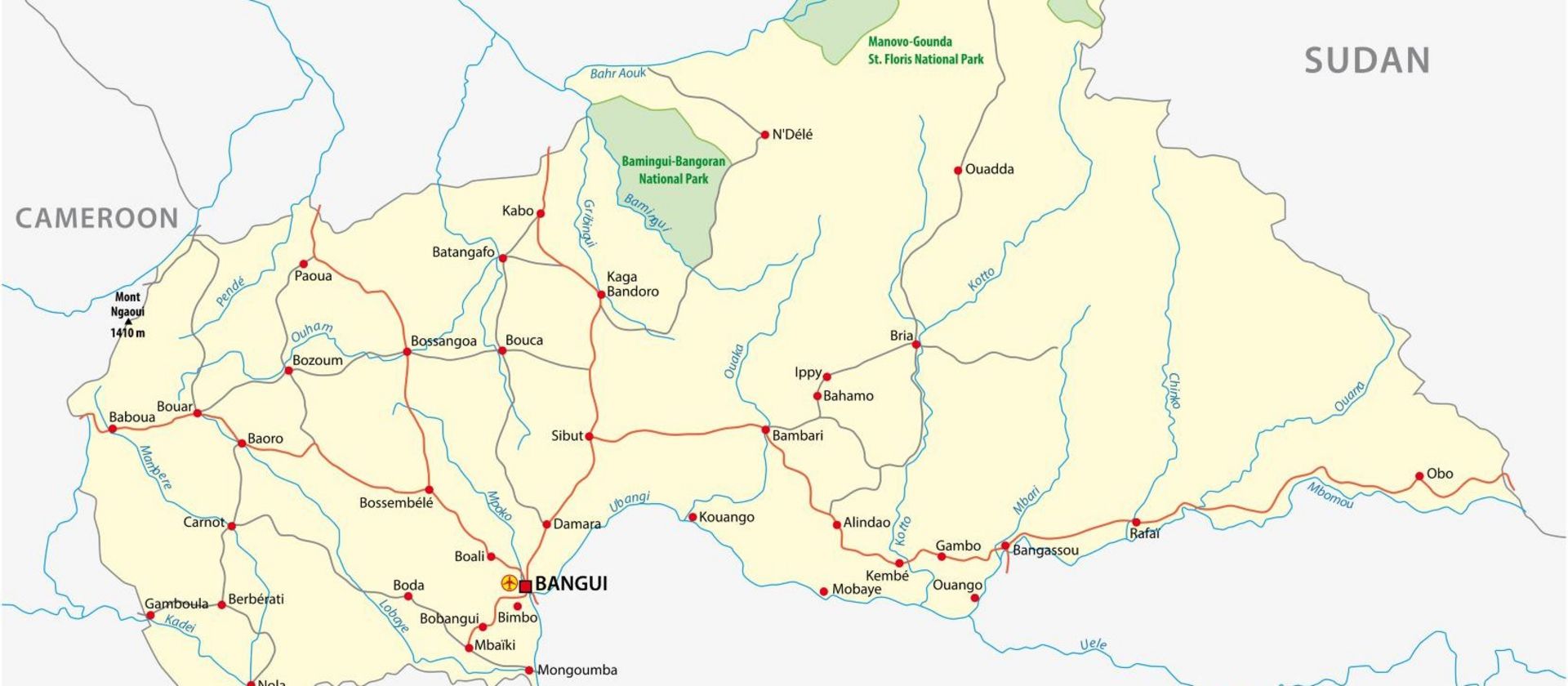

Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country that extends from the rainforests of the Congo Basin in the South to the Sahelian region in the North, on a territory larger than France. The country has suffered from decades of political instability and chronic violence, and this has resulted in its being one of the poorest countries in the world. Its 5.5 million inhabitants face harsh living conditions, including a high burden of infectious diseases worsened by limited access to medical care.

Fabian Leendertz, director of the Helmholtz Institute for One Health (HIOH) in Greifswald, has been working for more than a decade at the southernmost tip of the country, in the Dzanga-Sangha Protected Areas (DSPA). Within the framework of a close collaboration with WWF CAR, HIOH supports wildlife health monitoring in the DSPA, with a particular focus on Western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). Over the years, activities have expanded to also better characterize the human/animal interface and therefore human, animal and environmental health in this exceptional ecosystem.

The aim of this mission is to reinforce and formalize links with local stakeholders involved in public and animal health management, to present the forthcoming activities of the HIOH’s One Health Surveillance unit and to have an onsite visit of the DSPA and its current conservation and research infrastructure. The Helmholtz Center for Infection Research (HZI) is represented by the leadership of HIOH, including Fabian, Katharina Schaufler, Fee Zimmermann, Livia Patrono and Sébastien Calvignac-Spencer, as well as by Josef Penninger, scientific director of HZI. We are accompanied by Frédéric Singa, the head veterinarian of the DSPA, and Jörn Auf dem Kampe and Adrienne Surprenant from GEO Magazine.

The general director Yap Boum II provides us with an overview of IPB’s activities and objectives, and extends the friendly invitation to collaborate of our host, the scientific director Emmanuel Nakoune. Emmanuel, Fabian and Josef then leave for a discussion with the minister for research, who echoes the very positive feedback of the minister for animal husbandry. There is definitely a good interministerial vibe around One Health in general, and our initiative in particular.

During this time, a young malariologist of the institute, Romaric Nzoumbou-Boko gives the rest of the group a tour of the impressive facilities. IPB offers both biological analyses and vaccinations to the public, while also providing an infrastructure for research in infectiology, from medical entomology to molecular epidemiology. We leave IPB’s premises with the nice feeling we will be back.

At the dinner table in the evening our group is very excited: tomorrow we fly to Bayanga, in the DSPA.

In the evening we are invited for a barbecue by Thomas and Lena. The Swedish couple has spent more than 20 years in Bayanga, where they raised their kids (now all adults). Thomas has dedicated his life to bringing clean water to impoverished communities in the West of the country. Lena is a nurse who worked in the village but recently lost her job –international funding ran out, local needs did not. HIOH would be very lucky to recruit her on one of its ongoing projects, and we discuss potential plans.

Now, it is already time to head back to the capital. There, we will have two very interesting meetings over the next two days. We first meet the rector of the University of Bangui, Prof. Gresenguet. This university is the only public provider of higher education in the country, and it therefore plays an instrumental role in its development plans. We briefly meet with enthusiastic students, and promise to be back for a series of lectures. We also have the chance to meet Didier Kassaï. Didier is an illustrator who began his career in editorial cartooning in the late 1990s, and more recently chronicled the years of war in beautifully crafted graphic novels. He speaks very candidly about his life back then, further north, as he documented his daily life under gunfire. He has also used his illustration skills to contribute to public health communication projects, and we will undoubtedly call on him in the near future.

LeMonde article on the work of Didier Kassaï

After about ten days of intense meetings and discussions, we are traveling back to Europe, well aware of the privilege of being among the few to work in such a beautiful country, where people unfortunately have such a tough life. We will, of course, continue to develop our One Health surveillance project in the region of Bayanga, for the benefit of science and, more importantly, the populations.

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/1/6/csm_2_IMG_50681_cae320e1ef.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Ufer](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/b/e/csm_3_IMG_5094_1__753411be66.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Straße](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/a/a/csm_4-IMG_5161_500eb2e0a7.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Schild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/8/2/csm_5-IMG_5110_1__bbc0723ebe.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gebäude](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/3/0/csm_6-IMG_5107_1__427c54088e.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Baum](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/c/8/csm_7_IMG_21651_3f8f594fde.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/f/5/csm_8-IMG_5173_e1875b0aa7.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/6/6/csm_9-IMG_5268_42ed9c739c.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Elefanten](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/0/d/csm_10-AdobeStock_402336596_047fbdc03d.jpeg)

![[Translate to English:] Elefant](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/8/6/csm_11_IMG_5248_ecc7037dce.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Veranstaltung](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/d/7/csm_12-IMG_5316_e85f4b5fa4.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Fußballspiel](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/1/6/csm_13_142A2957_53d620f42e.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/1/e/csm_14-IMG_5338_63f9bf82ba.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gorilla](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/0/d/csm_15-142A2896_7445a2de4f.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gorilla](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/c/7/csm_16_142A2910_29cc7d910f.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/4/5/csm_17_IMG_5490__002__61e2716fc7.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/1/a/csm_18_142A3039_ee2b570328.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/f/1/csm_19_IMG_5516_f87bfd3c96.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gebäude](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/9/c/csm_20_IMG_5522_3f5e666431.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/0/3/csm_Bild1_dec47eaf3a.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/b/c/csm_Bild2_73ba275701.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/b/8/csm_Bild3_7d726dce60.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/4/f/csm_Bild4_b206fd6c1a.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Gruppenbild](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/d/9/csm_Bild5_d5bbcf2016.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Glaskugel mit Schema zum One Health Ansatz](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/6/3/csm_header_6000px-format4-3-150dpi_72_f8c5bcd651.png)

![[Translate to English:] Portrait von Prof. Fabian Leendertz](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/6/5/csm_Portrait-Fabian-Leendertz-Copyright_Stefan_Sauer_72_bf4b2ab673.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Portrait von Fabian Leendertz © Stefan Sauer](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/8/0/csm_copyright_Stefan_Sauer_72_1396ecab68.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Hauptgebäude der Universität Greifswald](/fileadmin/HIOH/__processed__/b/9/csm_copyright_Greifswald_University_Jan_Messerschmidt_c6f86932c5.jpg)